(StatePoint) Pregnant women don’t always feel they are safe and secure in cars today due to seat belts fitting differently on pregnant bodies. Researchers are posing the question, can the status quo be changed?

“The common misperception that seat belts aren’t safe for pregnant women surprised me,” says Juliana Said, a body design engineer at Toyota Motor North America R&D. “ Our team had an idea: can we help show that the designs are safe, while investigating areas for further enhancement?”

When Said and her colleagues started to look at the issue, they encountered unexpected challenges. There was limited research about the effectiveness of seat belts with expectant mothers or their babies. Additionally, there appear to be many third-party safety devices popular among parents that are untested and unverified.

But the biggest challenge is the widespread, erroneous belief among pregnant women and their families that seat belts are unsafe for a fetus during a crash – and that belief is so entrenched that some expectant mothers drive unbelted.

Statistics however show that when worn properly, belted pregnant women are much safer in crashes than those who don’t wear them.

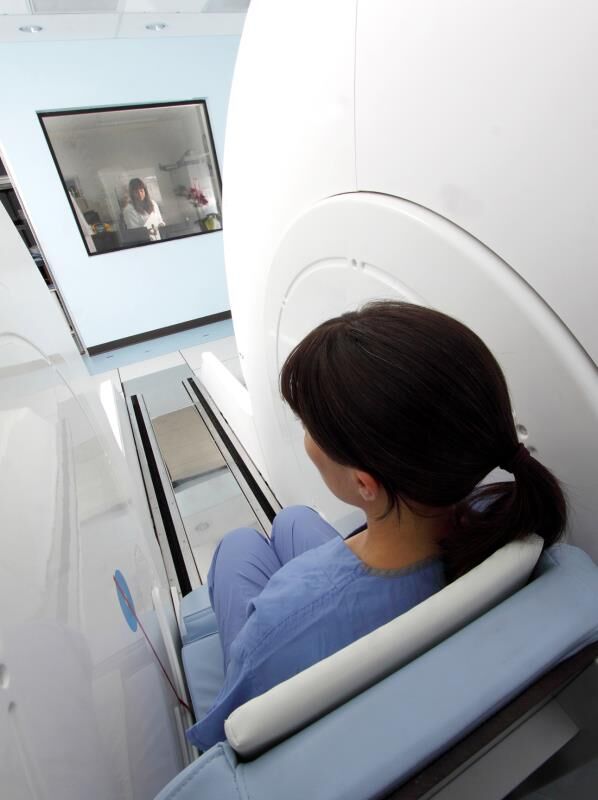

Said and her team started to work with Toyota’s Collaborative Safety Research Center (CSRC), which contracted with the University of British Columbia (UBC) for access to a specialized magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine designed to map anatomies of all sorts of body shapes in a seated position.

“While pregnant women properly wearing seat belts have better outcomes than no seat belts, there are opportunities through new research to further explore seat belt fit for pregnant women,” says Jason Hallman, senior research manager for CSRC.

The center and its research collaborators set about the task of creating data that engineers can use to potentially come up with future designs.

“We design seat belts using standardized dummies and processes,” Hallman says. “There’s no standardized dummy, no standardized tools available specifically for assessing pregnant occupant safety. Therefore, the industry doesn’t have a clear understanding of how future seat belts could better protect pregnant women or fetuses during a crash.”

Using this data, CSRC will create a computerized, three-dimensional model of pregnant bodies of different shapes and sizes in different phases of pregnancy.

The research project could help enhance one of Toyota’s research achievements, the THUMS digital crash injury model. THUMS is like a virtual crash-test dummy, constructed from painstaking research on different kinds of human tissue and how they react to crash forces.

The UBC research team devised a method to scan people seated in an automotive seat. A smaller MRI device is moved several times to stitch together different views until there’s an entire body image. Researchers are looking at how seat belts interact with bones and internal organs, and are excited by the data’s potential.

“We will publish this data with Toyota, and make it available to other injury biomechanics researchers, too,” says Peter Cripton, director of the Orthopedic and Injury Biomechanics Group at UBC.

The pregnant-body research and models may shed light on another top topic among parents: whether third-party devices designed for pregnant women add a safety benefit. These include pads to put on top of seat cushions, specialized lap belts and metal shields, for example.

“These devices may seem logical, but they’re not subject to the kind of rigorous testing used for seats, belts, airbags and car interior parts, and they may not be compatible with the way your car works,” says Said.

For more information about CSRC’s research, visit amrd.toyota.com/division/csrc/.

With better information in the future, pregnant women will be able to drive and ride in cars more comfortably and with greater confidence.

*****

Photo Credit: UBC Upright Open MRI Research